Photos: Simon Schnocks

Today we’re going to Antwerpen. I’m visiting the Belgian artist Anne-Mie van Kerckhoven in the Borgerhout district. Her retrospective that is currently displayed at the Museum Abteiberg Mönchengladbach <em>What would I do in orbit?</em> provides a unique insight into her multimedia oeuvre, consisting of drawings, music, paintings, computer and video art. Impressed by the aesthetics of this show, during my visit today I would like to find what ideas and motivations lie behind her works.

22/12/2016: A busy main road takes us to the quiet residential neighbourhood where the artist’s house can be found. It is unobtrusive amongst a row of bourgeois houses. To be sure, I take another look at the business card. The street name and number are correct. Doorbell label? It’s right too. Let’s get started! We ring the bell. The door opener buzzes. The narrow hallway gives a first surprising impression of the individual character of the house. Up the stairs there is the cosy kitchen leading into the living room, where we (my son Simon and I) are invited to coffee and pastries.

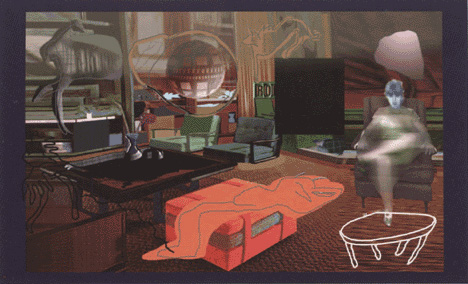

The room immediately reminds me of one of her paintings. Colourful walls, a green sofa, a vintage looking sideboard and dining table, above the sideboard a tarnished mirror hangs crookedly surrounded by album covers, postcards, and trinkets … Anne-Mie van Kerckhoven in the middle as in one of her self-portraits. It’s a pity I can’t take pictures here …

Rorty, 2002

We talk about her exhibition in Mönchengladbach. I had prepared a little by reading the museum’s visitor brochure. The brochure is a work of art in itself. Van Kerckhoven did not only write the content, but also designed the layout. She has divided her life’s work into 12 chapters, for which there are also 12 exhibition rooms. Speaking of the exhibition rooms – the architecture that was built there for the exhibition was developed in cooperation with an architect. “It was a crazy challenge to contend with this dominant museum architecture. The house itself is a work of art. I felt like my art was in competition with the room. Walls that were not quite straight, no set visitor paths, only a light-filled open plan … We had to build a model to always have the dimensions and proportions of the room in front of us while planning. A floor plan was not enough,” she explains, expressing her initial doubt.

Impressions of the exhibition What would I do in orbit? (Photos: Image 1: Achim Kukulies, Image 2: Detlef Ilgner, Image 3: Uwe Riedel)

“Why were there 12 chapters? Is the number 12 important?” This question sets off a firework. Of course the number is important! Numbers, symbols, characters, and words play a central role in her works. “That was certainly no coincidence. I searched desperately for any measurement to systematise this huge collection of 40 years. Out of the initial 27 chapters, I somehow ended up with 12. And that’s the exact number that we encounter in all cultures as a cosmic number. Our world lives in rhythms of 12: one day is 2 times 12, in 12 months the Earth orbits the sun … But as is often the case, this did not happen on purpose with me. There were simply 12 chapters at some point. Almost everything happens intuitively,” is her answer.

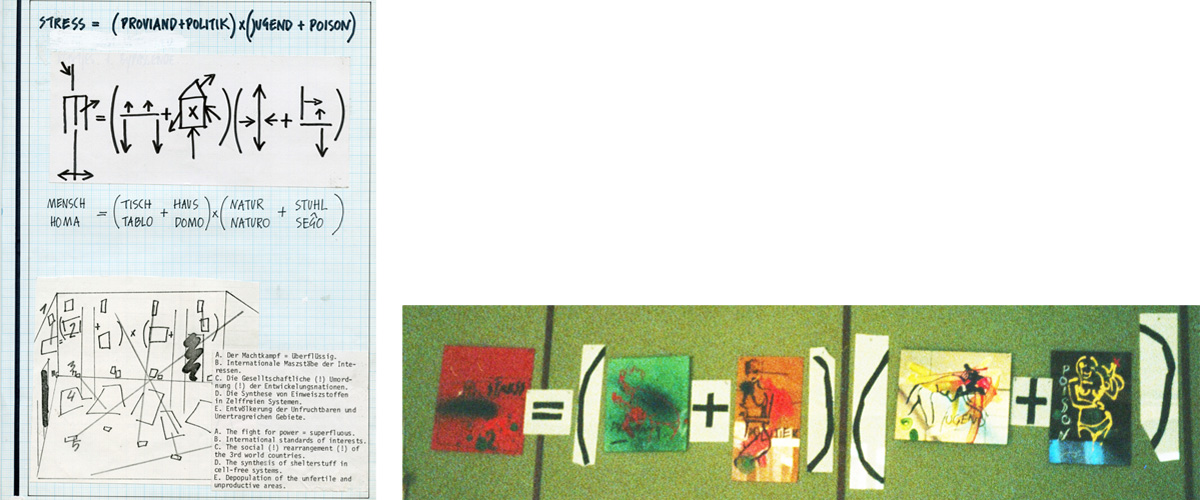

“Don’t intuition and systematisation contradict each other?” I ask. She considers briefly. “It sounds contradictory at first, but maybe I need to explain it differently. I look at the world very closely. Nothing is just the way it is for me. I always want to know why it is as it is. I experiment with my perception and my consciousness. There are, for example, certain words, headlines, or pictures in books and magazines that I perceive intuitively separately from their original context. As soon as I still feel indefinable thing, an almost inner compulsion to pursue these intuitions develops in me. I then write down words or cut out text and images, and through this action transport the formerly intuitive thoughts in my mind. At this moment, however, everything is still confused and disorganised. In the next step, I look for new contexts in them and thus systematise my thoughts. The words, signs, and images are then artistically put into new contexts by me. I decode images so to speak, and then encode them again. In this way I can control my thoughts and give them a logical position in my life.” ‘Logical position’ makes me think of mathematical formulas and I immediately remember works that I’ve seen by her.

Image 1: Printed from Journal, 1994 Stress = (Proviand + Politics) x (Youth + Poison) – Image 2: Installation, 1981

In this context, her typical collages can now be explained, in which fragments of different types of communication are combined. Torn from their previous context, decoded and re-encoded in artistic imagery, van Kerckhoven looks behind the surfaces. She wanted to trace the “True and Original” that lies dormant in our subconscious, she explains. This motivation is also reflected in her drawings and paintings. They often appear as multi-layer montages, in which the viewer must dig to the origin level by level. Much of it looks like it developed spontaneously and by chance. But often it is also as if she was trying to schematise her figures and forms and follow a system of order.

Intuition and systematisation – there they are again, the basic pattern.

An almost infinite variety of topics can be found reflected in van Kerckhoven’s work. Mythology, philosophy, religion, politics, science, technology … no topic is too complicated for her.

Image 1: Fragile, 2011 – Image 2: Attributen en Substantie, 1993

Emblematic of this is the following story that she relates with a laugh: “In a conversation with a neuroscientist I took note of the words which I found “beautiful”. I understood nothing, really absolutely nothing about the content of this conversation! Based on these words, I then found myself sometime later drawing an installation with amusement, which in my eyes was simply good. I had, as I said, only collected the items for their aesthetic useful basis. And then the unthinkable happened: the scientist mentioned looked at the installation, came up to me enthusiastically, and said that his thoughts had never before been so well captured and visualised. That was for me the proof that our perceived world is only an image and many diverse ideas must be hidden behind it.”

The question of how communication effects human action, or more specifically, how our brains process information, noticeably propels the artist.

Before she shows us her workspace now, she apologizes in advance for the disorganisation and that at the moment she can’t show us much work. “It is almost everything in Mönchengladbach. It has not been until this week that I can slowly begin to clean up and make room. I always first need fresh order as a basis before I can start with something new. It makes me very uneasy that everything is so chaotic at the moment.” Just as she must assign a logical position to her chaotic thoughts, she must do the same with her physical environment, I think.

Through the kitchen and over the roof, it leads to the building in the back where her office is. A narrow steep wooden ladder leads from there up into the attic, where the studio used to be. Throughout the space there are numerous books and magazines distributed that the artist likes to read.

… on the way to the office and insights into the workplace

Her studio is within walking distance. Although perhaps not everything is in its proper place, there is no trace of “chaos” here. Based on the different work materials, it is evident that the spaces are divided according to the work processes. One room is for drawing, another for collages and montages, in the next room small formats are archived on shelves and large formats are kept in the front on the door. “Is there an order in which a work develops? First the drawing, then the collage, or is there perhaps an initial draft?” I ask. “No. No. Everything develops intuitively, almost simultaneously,” is the almost indignant, predictable response. How could it be otherwise?

Image 1: … in the studio – Image 2: Elke Backes and Anne-Mie van Kerckhoven

Together we are looking at a folder with current drawings. Leafing through, I realise that all the work that I’ve seen of her somehow radiate something powerful and direct, regardless of the genre, and also regardless of whether they are designed delicately and like a sketch or powerfully and expressively. There is something combative, colourful, loud in them. Like the artist herself. Looking back on our conversation, I realise that she is fighting against mental laziness, against stupid human action, and especially against preconceived knowledge. It is only logical that self-portraits can so often be seen in her work. Likewise, it is logical that she does not expect us to decipher her codes. On the contrary! She wants her art to awaken our own thinking, our own experiments of perception and consciousness. Simply to encourage, to question deadlocked worldviews – world images.

In conclusion I therefore propose doing van Kerckhoven self-experiment in three steps:

Step 1: Visit the exhibition What would I do in orbit?! (until 26/2)

Step 2. Accept that the mind wants to be “aroused”!

Step 3: Find your own codes to decrypt!

MORE INFORMATION

about the artist: http://www.amvk.be

about the exhibition in Museum Abteiberg: hier klicken

about lecture and talk with van Kerckhoven in Museum Abteiberg on 2/2/2017, 8 p.m.: hier klicken

about concert with van Kerckhoven in STEP in Mönchengladbach on 11/2/2017, 6 p.m.: hier klicken