Text: Dr. Elke Backes, Studio-Photos: Carsten Sander

Her photographic portraits of artists not only document the who’s who of art history. More than that, many of these very images themselves have become icons of photography history in the genre of artist portraits. Whether Joseph Beuys, Gerhard Richter, Andy Warhol, Sigmar Polke, or Hanne Darboven – Angelika Platen always manages to capture the person behind, or even with the art. How did her career lead to these encounters? She tells me all about this in an exciting journey through time, beginning in the late 1960s, in her studio in Berlin-Charlottenburg …

Angelika Platen

E.B.: Let’s start with the obvious question: what led you to photography?

Platen: I actually wanted to study architecture. But love drew me from Hamburg to Berlin, where this course of study wasn’t available at the time. So, I decided to study Oriental Sciences, but then I got pregnant after starting my studies. That was it for the time being. Back then, you couldn’t go into lectures with a big belly. When my daughter Antonia was born, I bought my first camera and photographed only her. That was the beginning.

E.B.: Didn’t you study photography in Hamburg?

Platen: Yes. That became possible shortly afterwards, because my husband started working as a cultural reporter for stern magazine, and we moved back to Hamburg. In the meantime, shortly after the move, I had my second child, Katja, and was thinking about what to do next. I wanted to be independent and have an interesting career. With the idea of becoming a professional photography photographer, I enrolled in the photography class at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg. It took only a few weeks before I set up a darkroom and quickly began photographing at art exhibitions and fairs. I then took the initiative and offered these images, which were still documentary in nature, to newspapers such as Die Welt, Springer Verlag, and Der Spiegel, and slowly made a name for myself. This led to me being commissioned by Die Zeit to oversee the art as commodity page and write articles about new editions.

E.B.: Was that your door-opener to the artists?

Platen: Yes. Most of them were not yet well known, and a publication could help bring them to the attention of galleries or exhibition organizers.

f.l.t.r.: Gerhard Richter (1971), Günther Uecker (1972), Konrad Klapheck (1971)

E.B.: Were the artist portraits commissioned works?

Platen: Just like the documentary photos, these were also created exclusively on my own initiative. I didn’t go to the artists with the aim of publishing the photos. Rather, it was out of a great curiosity to learn more about art through conversation and at the same time get to know the people behind it. When taking portraits, my goal was to combine both. To understand this, it’s important to know that art and photography were not yet considered equal genres at that time. Initially, my work was therefore more of a photographic experiment. When I enlarged a photo of Joseph Beuys in Eindhoven in 1968 and another of him that same year with Rodin’s sculpture, I knew: Now I’ve got it.

Joseph Beuys (1968)

E.B.: So, you were right at the heart of the art scene and had gained a recognition that would then lead to the next step in your career?

Platen: Yes, and it was probably in this context that I received the surprising call from Gunter Sachs’ office. What was even more surprising was what happened next: I was invited to an interview with Gunter Sachs on Sylt. Sachs, known at the time not only as a photographer but also as a playboy, stood waiting on the airfield with his motorcycle. When I refused to sit on the back seat, he drove off and simply left me standing there. It looked as if I had lost my chance. Fortunately, his private secretary took over the conversation and informed me of the actual reason behind my visit. He told me about plans for a new gallery in Hamburg and suggested I take over its management. The offer came at just the right time for me. I had separated from my husband, was a single parent, and needed a regular income. At the same time, it was literally a leap into the unknown. From this perspective, I had never had anything to do with art before.

E.B.: As a gallerist, did you still have time to take photographs?

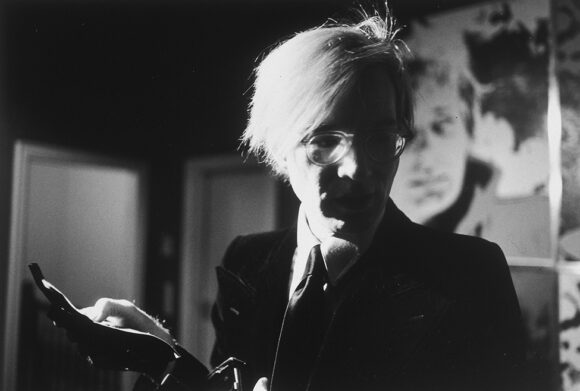

Platen: Not much, actually. But it was too tempting not to capture these special moments – such as the first opening with works by Andy Warhol. Warhol had traveled from New York especially for the occasion, Hamburg’s art world was at Gunter Sachs’ feet … I just HAD to use my camera amid all the hustle and bustle.

Andy Warhol (1972) at his exhibition opening in Gunter Sachs’ gallery

Platen: Yes, it did. But not in regard on my career as a photographer – because from then on, I had special access to the contemporary artists of the time.

When Gunter Sachs decided to close the gallery in 1976, a completely different encounter in Saint-Tropez led to a 20-year break in my photography career. At first, everything was like in a movie. I met a special man in a bar. We met on his yacht, and later at his estate in Paris. To make a long story short: we married in 1978, I moved to Paris with my children, worked in his company there, and gave birth to my third daughter, Julia.

E.B.: So, you had three daughters, and worked at the same time?

Platen: I never lost sight of the importance of being independent. At a time when women were not allowed to have their own bank accounts, I made it my priority to secure that essential condition for myself. The fact that I was able to invest my monthly salary wisely would later prove to be my great fortune. When I found out about my husband’s parallel life years later, I had the financial foundation to leave him and return to Germany.

E.B.: How did you reconnect with the art scene?

Platen: Two things came together: First, my children asked me what I actually wanted to do with my photos from the 60s and 70s. That was the impetus for my first monograph, which I was able to publish with Stemmle Verlag. Second, the curators of the exhibition 30 Years of the Art Market, on the history of the Cologne fair, asked me for photos. So I was back in the conversation, bought a new camera, and from 1998 continued my portrait series.

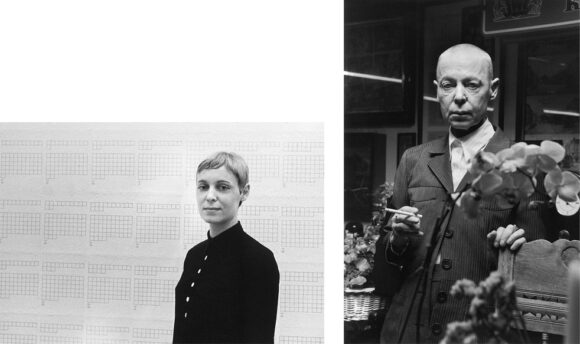

E.B.: Looking at your pictures, there are some artists you photographed again after a long interval. One photo stands out in particular: it is the now-famous portrait of Hanne Darboven, who, suffering from cancer, seems to pierce the camera with her sublime gaze.

Hanne Darboven 1968 and 2002

Platen: This photograph is one of my favorites. After our first meeting at her exhibition prospect 1969 in Düsseldorf, which marked the beginning of her career, I asked her for another meeting 33 years later. It was a very warm encounter, but the portrait I had in mind took a while to materialize. She sat in a dark corner, wearing shirt and suspenders. As always, I worked without extra lighting, and at some point realized I wasn’t going to get good shots that way. So, I finally said: Hanne, if you don’t get up now, put on your jacket, and stand right here, it is not going to work. And so, I managed to capture this very special, very brief moment.

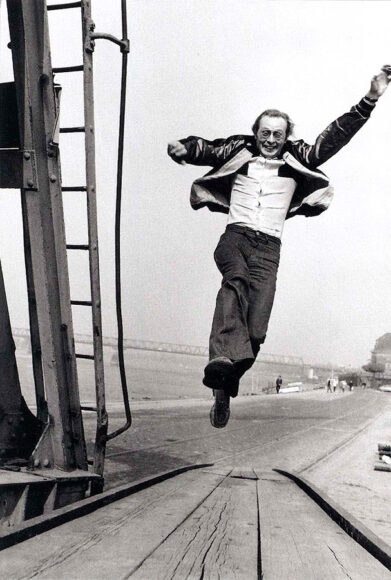

E.B.: Speaking of special moments – how did you manage to catch Polke in mid-air? That’s another one of your iconic shots.

Platen: Polke was a playful guy. Not far from the Düsseldorf Art Academy, he had thrown himself onto a seesaw with childlike enthusiasm, and I climbed onto the nearby scaffolding to photograph the scene from above. When the seesaw suddenly shot up and he flew into the air, I kept shooting and got damn lucky. Once again, it was the right moment (laughs).

Sigmar Polke (1971)

E.B.: You now have numerous publications to your name. One book is particularly significant in that it focuses exclusively on female artists. Was this a way of making up for lost time?

Platen: Actually, at some point I realized that I had mainly photographed male artists. That was simply due to the times, when women were completely underrepresented from the art scene. When the MeToo movement emerged in 2018, I spent a year photographing exclusively women artists and later published the book “Meine Frauen” (My Women) with Hatje Cantz Verlag.

f.l.t.r.: Cornelia Schleime (2000), Monica Bonvicini (2012), Marina Abramovic (1999)

E.B.: What will happen to the vast archive you’ve accumulated over so many decades?

Platen: I’m currently in the process of cataloging my estate. The concept with the corresponding chapters is in place, and I’m filling the chapters with content. My wish would be for this inventory to be carried out as a student project. That’s still on my to-do list …

E.B.: I suppose the next exhibition is already coming up?

Platen: Of course (smiles). The exhibition ANGELIKA PLATEN. “Einen Augenblick, bitte!” (ANGELIKA PLATEN. One moment, please!) will open at the Museum Ratingen on October 10, 2025.

Angelika Platen, portrayed by Carsten Sander

Further Information

Website: https://angelikaplaten.com

Publications: https://angelikaplaten.com/data/publications/

Next exhibition: ANGELIKA PLATEN. Einen Augenblick, bitte! at Museum Ratingen, October 10, 2025 – January 25, 2026, Museum Ratingen Instagram