Today I am going to Amsterdam. More specifically, a little further than Amsterdam, to the tranquil little town of Koog aan de Zaan. Located directly on the river Zaan is the former Hong-Fabriek [honey factory], which is a place for creative entrepreneurs nowadays. I am going to visit the Dutch artist Jasper de Beijer here. His art, which can be categorised as photography, and which can be more closely described as “manipulated photography”, is now receiving international recognition through gallery and museum exhibitions and has already become a part of significant public collections. In my studio visit, I would mostly like to find out how his pieces are created, and against what background. I will be accompanied by my friend, the photographer Sarah Schovenberg, who is taking over the photographic documentation nowadays.

Alternative and individual are the first words with which the Hong-Fabriek can be described, both from the outside and the interior. We will be picked up by the artist in the courtyard. Passing unusually designed furniture which was probably created here, we make our way to the freight elevator, which clearly has its best years behind it. Expectantly, de Beijer presses the button: “The elevator only works some of the time.” We wait. Surprisingly, it is not working now. So, we walk up to the fourth floor. On the way there, we receive our first piece of information. The formerly large open space of the fourth floor has been divided bit by bit into separate rooms, reported de Beijer. Size and location should be determined here and expanded as needed. Loud banging and construction materials in every corner unmistakably suggest brisk construction activity.

He had initially marked out his work space, de Beijer told us while opening the door, then directly bricked up the exterior walls and eventually expanded the interior too. Upon entering the room, it is then revealed to us then what everyone imagines a real art studio to look like: boxes piled up between fabrics, paint tubes, paint cans, glue, styrofoam and paper. Other items such as luggage, lampshades, rattan baskets, costumes and artistic plants are lying around everywhere.

Studio impressions …

In the middle of all this, I find figures which I recognise from his pictures, but in miniature.

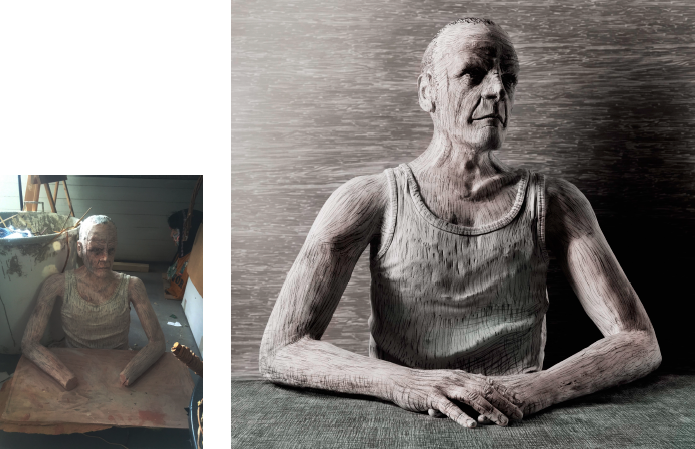

Model and photo from series Marabunta, 2012

Model and photo from series Mr. Knights World Band Receiver, 2012

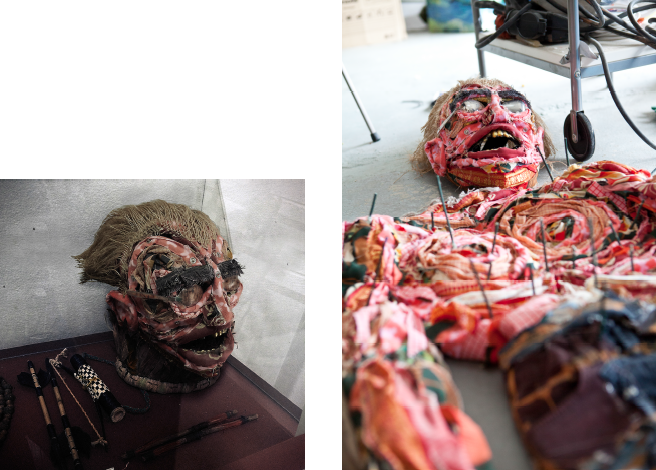

There is creative chaos. On closer inspection, however, I realize that there is a system in the chaos. Different workspaces are divided not only by rooms, but also reflect the parallel work processes of de Beijers, which I’ll find out about later. The walls covered with green fabric in a corner of the room, which are equipped with a floor, ladder and tripod, suggest his photo studio. The model airplane made of rattan placed in the centre of the room, the models of heads standing and lying on the trestle tables, ships, cars, hairpieces, the colours and the tools refer to the analog part – while the computer, printer and camera at the other end of the room refer unmistakably to the digital part of his work. At least I was able to sense, how his manipulated photographs could come into being. I glance up at the gallery, which had been drawn into the room.

He had not drawn this in only to gain additional storage space, but also to create a separate relaxation area, de Beijer told us, following my gaze. The hodgepodge of discarded upholstery located underneath the gallery next to the table is apparently there for taking short breaks or, as now, for having meetings with visitors. There is chocolate and water from a cola bottle.

Our conversation begins.

Jasper de Beijer and Elke Backes

De Beijer got started. Collecting his thoughts and ideas together into words, he explodes: “I want to break patterns of perception. To create awareness that the images to which we are constantly exposed are only five percent real, and about ninety-five percent are influenced and complemented by our individual memory, and especially by the collective memory. ” He remembers the situation that brought him to the attention of this awareness. “My wife is Indonesian. A variety of photos at home remind her of old times in her homeland: portraits, landscapes, houses … These pictures or images which I recognised from film documentaries, books and stories had obviously shaped my image of Indonesia. I only realised this during our trip there. Although I knew, of course, that everything there had changed, I felt irritated and confused at the sight of the noisy cities. The image in my mind was stuck in the colonial period and was desperately looking for traces of the past. I then discovered an old colonial house, where I developed the idea that has defined my work from then up to today. I wanted to reproduce objects from past times, so that they can be placed in different times or environments. So, I photographed this building from every angle, firstly digitally mastered it in my studio, and then converted it to scale as a model using this template. Next, I took some of our portraits to use as a template for modeling face masks and photographed people in contemporary clothes, but with this face mask. Recently, I created a digital fantasy landscape for the building and then I brought all the items together in new scenarios. In this way, it was possible for me to construct alienated atmospheres.” [Here, he describes the project Buitenpost, 2004]

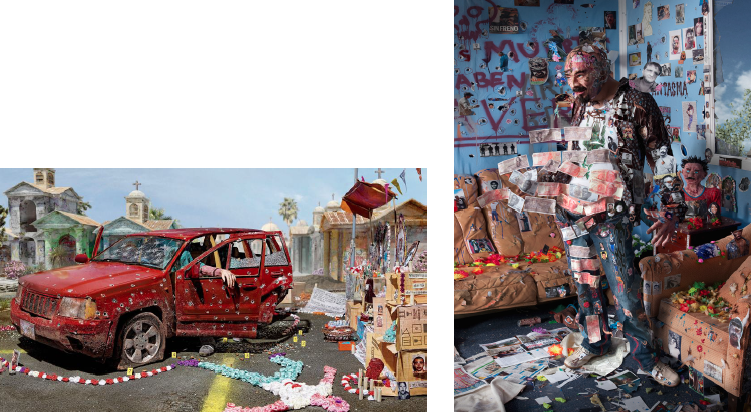

First of all, I try to portray what was going on in my head when I encountered one of his picture series for the first time: “I thought at first: ‘Wow! Cool designs and colours’. Their aesthetics reminded me of computer games. The question of technology was accordingly superfluous. But of course – they could only have been designed digitally. On closer inspection, however, I was then uncertain. Individual fragments of images seemed assembled, and collage-like. They did not fit together. I wondered whether there was an intention behind this, and I felt curious. It was the series <em>Marabunta</em>, which dealt with the Mexican drug wars. As I then found in your other projects, your work is always defined by cultural or socio-political issues. – How is everything connected now?”

Examples from the series Marabunta, 2012

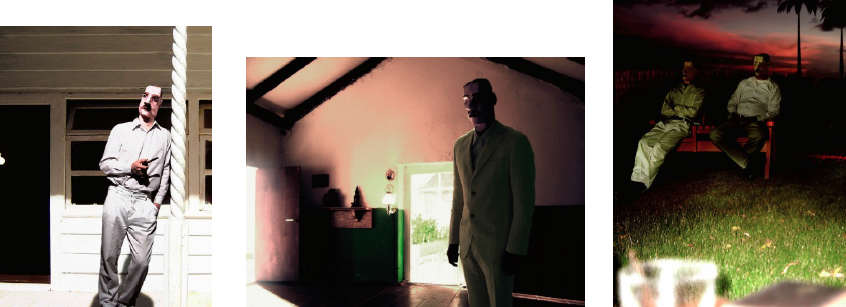

Examples from the series Buitenpost, 2004

Getting to grips with what is imprinted on our collective memory and which objects or even myths from the past are represented, has driven him since then. His current project, which is still under development, goes a step further. In <em>The Brazilian Suitcase</em>, he told me that he had to make a journey across time in three stages (1926, 1979, 2016). The photos and documentation about the legend of the British explorer Percy Fawcett, who mysteriously disappeared in the Brazilian jungle in 1926, inspired him to portray three different time periods, in a mutation of the location, civilization and the research results, as was caused by the research of Fawcett and all successor expeditions in this region: “And this is symbolic of all expeditions. While seeking the original, everyone must someday realise that once it has been explored, a site can no longer be original. Everything has evolved and changed. They dig and dig, desperately seeking the traces of the past in order to ultimately achieve, at maximum, the same starting point of the first body of research. It is a recurring cycle. Myths and images characterise expectations that cannot be fulfilled.”

Examples from the project Brazilian Suitcase, 2016

Actually, this is comparable to his expectations of the trip to Indonesia, I think. Just as the documentary photos of Percy Fawcett are considered to be <em>real</em> contemporary documents and illustrations of originality by all subsequent researchers, the family photos at de Beijer’s home were viewed by him as images of the original Indonesia. Since then, he has also become a researcher on the original images of different cultures. But it is only this? Is he perhaps superficially researching the power of the image as such? Does he not, in principle, bring the objectivity of documentary photography into question?

Are realistic presentations in the museum photographed or manipulated?

I remember his pivotal statement at the beginning of our conversation. He aimed to create awareness with his work, that the images to which we are constantly exposed, are only five percent real and about ninety-five percent are influenced and complemented by our individual memory, and especially by the collective memory.”

How this intention could be better visualized than by a clear collage, became abruptly apparent to me. Therefore, his pictures were put together from a fraction of reality and a great amount of fiction! He invites us as viewers on a journey of exploration into our own consciousness. We must explore which fragmentary images in his photographs bring up memories and/or moods in ourselves. Images that we had perhaps previously stored erroneously as real pictures in our memory. Everything constantly revolves around the question: What is reality and what is fiction?

De Beijer is a dreamer for the most part, and a little bit of a realist too, as he describes himself. It’s amazing and wonderful to see how such a character can find his reflection within art …

More Information

Preview: Exhibition The Brazilian Suitcase, January 2017, Galerie Ron Mandos, Amsterdam

… about the gallery: http://www.ronmandos.nl/

… about the Artist: http://debeijer.com