Photos: Sarah Schovenberg

Today I am visiting the concept, action, and installation artist Helmut Schweizer. In his search for cross-border boundaries in art, influenced by the art discourse of the 1970s, his work finds its aesthetic realisation in a wide range of different media and materials. The works of the documenta IX participant are regularly displayed in museums and are part of many international collections. His installations in particular awakened my curiosity, which were more reminiscent of scientific laboratories than situations in art exhibitions.

We are meeting in his studio in the district Flingern of Dusseldorf. The studio is located in a classic old building whose imposing stucco ceilings dominate our introductory topic. From the ceiling, my gaze slowly descends, and then remains on the countless sculptures on the upper kitchen cabinets. The long wooden table in front of them seems to be the only piece of furniture where space has been cleared. The otherwise fill-to-bursting space extends like a hall towards the garden and ends with a little romantic winter garden, whose architecture reminds me of Paris in the 1920s. Ceiling height shelves, equipped with folders, books, sculptures and a lot of miscellaneous items mark the walls on the left and right. … and in the middle of the room there is a special kind of scenario.

In the semi-dark, very modern equipment for digital image processing is combined with an unmanageable amount of sculptural shapes, which seem to combine the most diverse laboratory glasses into trial arrangements. The toxic, colourful, and aggressively luminous substances inside the fragile glasses threaten an imminent explosion. Altogether, a scene between secret research facility and witch’s kitchen. What is happening here?

Impressions of the studio …

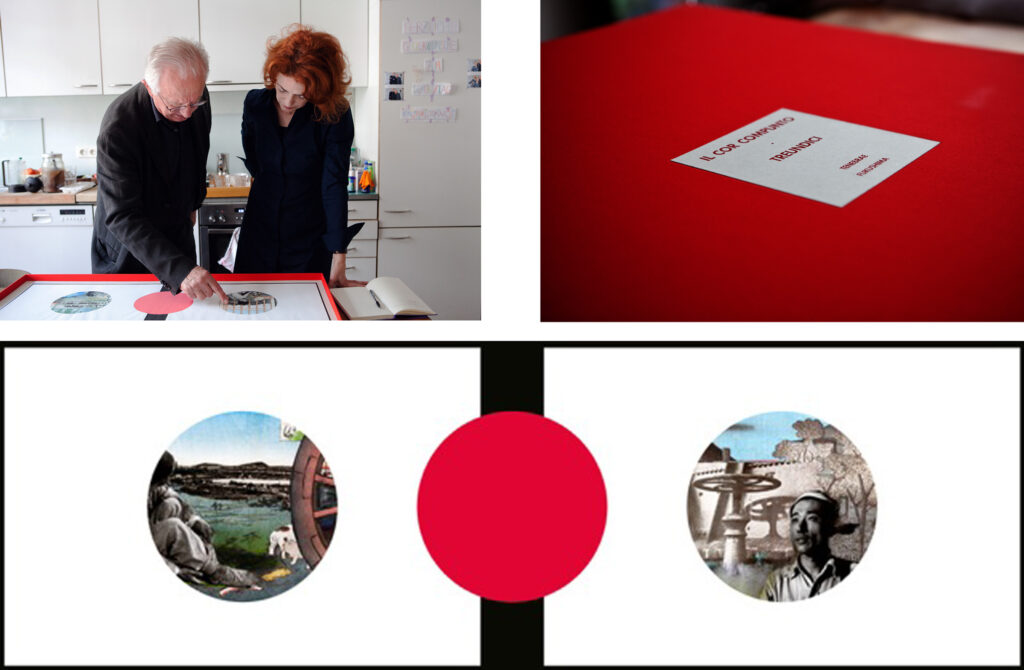

“To get started,” Helmut Schweizer suggests, “we can look at some of my graphic portfolios. After that, my work will make a lot more sense.” No sooner said than done. A large portfolio, wrapped in a sophisticated red textile, is spread out on the long wooden table in front of us. After the silk paper is carefully pushed aside, the first single sheet of the IL COR COMPUNTO work is presented · TREUNDICI. The work includes a series of three folders. The individual sheets of the first series are dominated by a vermilion sun, which radiates towards the viewer in the central position of the transverse format, contrasting with the bright base of the hand-made Japanese paper. It is flanked in the same size and in the same format by delicate beautiful graphics. Japanese coloured woodcuts of a “healing world” – right? I stop shortly for a moment. On closer inspection, collages of black-and-white photographs are discernible. Mounted so finely in the picture, the transitions partly manually overdrawn, I did not notice them at first. They are images of horrors. Time documents of destroyed nature, destroyed culture. There are pictures of the disaster of Hiroshima. And we find ourselves in the midst of it. The theme and guiding principles of Helmut Schweizer’s work.

First paper (Kyoshi) of the series NEL TARDO ROSSO INDIETRO NEL FUTURO of the work IL COR COMPUNTO · TREUNDICI (Digital print on Japan paper)

“When I began working as an artist, I was concerned with the changes and destruction of nature and culture caused by technology and civilisation,” says Schweizer. “In particular, the results of nuclear physics research, which on the one hand have led to technical progress, but on the other hand also to the development and use of atomic bombs and response catastrophes; they move me and challenge me repeatedly to artistically address this humanity-threatening topic.” This explains the poetic sounding title of the work, the translation of which triggers anxieties. It is coding in Italian which reflects the artist’s emotional state on the day of the catastrophe of Fukushima: IL COR COMPUNTO (the collapsed heart), TREUNDICI (3/11 = the date).

We talk about the design of the work. The format and the red sun are reminiscent of the Japanese flag. “It is the exact measurements of a children’s Japanese flag,” I learn. “Was the format planned from the start?” “No. The idea developed during the course of finding the picture. Just as everything develops as a process with me. The starting point of the whole series were published photographs of the American nuclear authority on the effects of nuclear weapons and press images of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan, which I had collected over decades. In this, as in all my works, I looked for references to music, literature, and fine arts. The poem Im Spätrot by Paul Celan and Walter Benjamin’s interpretation of the Angelus Novus by Paul Klee were my inspirations for the design and content. According to Benjamin, the angel unmasks Angelus Novus as a catastrophe, much of what was once considered progress. It is a look at the future, which is directed backwards. For me, this idea finally formed the starting point of the story I wanted to tell,” says Schweizer.

“Then I looked at the press images again. This time, however, in an abstracted way. Suddenly, I remembered some shapes or fragments from Hiroshige’s coloured wood pieces [Utagawa Hiroshige was a major 19th century Japanese painter – E.B.] In the next step, I began to try out how collages of these woodcuts coincided with collages of the press pictures and immediately felt that their combination visualised the right entrance into my story. Untouched nature from pre-industrial times and destroyed nature and culture from the time after the nuclear catastrophe merged together in an image plane,” Schweizer says about the development process of the first collages series.

“The children’s flag seemed to me the ideal basic element in its format and image statement. Only the right paper was missing. The material is always very important to me, since every type of material also has its own story. I then began to try to print the red sun on Japanese paper. This was very difficult. The soft, very thin paper ripped quickly and absorbed a tremendous amount of colour, which greatly impaired saturation. So I experimented for a while until the result satisfied me. And during this experiment, I realised that the repetition of the roundness of the sun with the collages embedded was somewhat like a vew from a window – like from a porthole. And this was an association that was a wonderful way to look at the overall statement, looking backwards to the future”, is how he explains the development of the format as well as the special significance of the material.

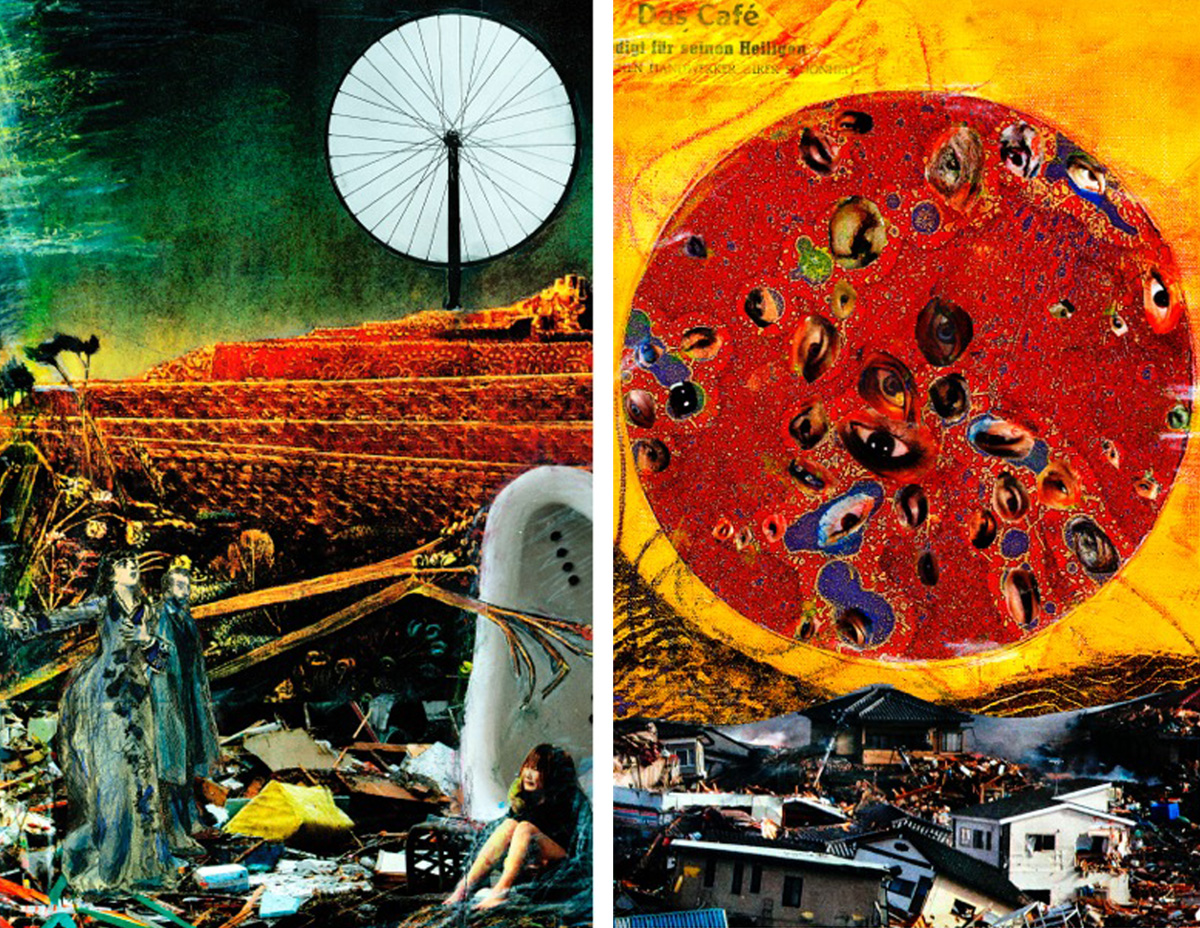

The two other folders are in portrait format. The second series has the addition of TENEBRAE · FUKUSHIMA. “Tenebrae refers to a particular Christian worship service that, in Holy Week, symbolises the suffering filled with fear with symbolic rituals of darkness. I once coincidentally experienced this sort of worship in Italy. It was incredibly disturbing,” says Schweizer, explaining the title. In this series, the press pictures of the Japanese catastrophe in Fukushima merge with excerpts of surrealistic works by Max Ernst, Man Ray, and Marcel Duchamps. Contrary to the delicacy of the first series, the compositions created here appears imaginative, loud, colourful, intrusive, disturbing …

Examples of the second series TENEBRAE · FUKUSHIMA of the work IL COR COMPUNTO · TREUNDICI (Digital print on Japan paper)

Finally, the third series has the additional title ECCE HOMO · PER ETTORE MAJORANA. Again, a coding. [Ecce homo = “Behold, a man,” Ettore Majorana is the name of an Italian physicist] Just as in the first series, the silhouette of the sun set the template for the collage, in this series it is the silhouette of the Minister of State who at that time regularly publicly announced the latest results of the Fukushima disaster. In the collage he appears to be gradually changing and finally dissolving. The respective backgrounds of the individual collages form romantic skies from Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings.

Beispiele aus der dritten Serie ECCE HOMO · PER ETTORE MAJORANA des Gesamtwerks IL COR COMPUNTO · TREUNDICI (Digitaldruck auf Japanpapier)

“The story of the angel, looking backwards into the future, has a good ending in spite of everything,” I try to interpret the last page. “Good is perhaps overstating it. It’s an open ending, but a hopeful one. And this also matches the whole credo of my work: I do not want to look backwards into the future, but forward … with images of hope,” says Schweizer.

We go into this credo in more depth with coffee and cake in the winter garden.

But that is not all. I would like to learn more about the installation “Experimental designs”, which we are now standing in front of. Labels are attached on it with names such as Marie Curie, Otto Hahn, Enrico Fermi and Edward Teller. “These are names of important chemists and physicists, the installations are their portraits,” is the answer. Each contains an allusion to the work or person portrayed, Schweizer explains lightly. The material description, which I find later in a catalogue [1] awakens repressed memories of my physics lessons: beakers, tubs, cylinders, petri dishes, metal discs, mirrors and glass, piston rings, metal weights, rubber, gelatine, water, glacial acetic acid, uranium … The transition of physical and artistic fields of experimentation seems to be fluid here.

[1] Helmut Schweizer. Laboratorium. 1969 – 2010. Hg.: Barbara Hofmann-Johnson u. Susanne Pfleger. Wolfsburg 2011, S. 52.

Speaking of the experimental field: Based on a series of collages based on experiments in the inkjet printing process, Schweizer developed two production cycles on the basis of a further collagen series that were used in experiments with other carrier materials. Each titled with the name of a radioactive element or isotope, 50 collages combine photographs of various atomic devices and disasters with fragments of images by Giorgio de Chirico and Venetian paintings. The silhouettes of animal images are also clearly recognisable. “Why Venetian paintings in particular? And what is the meaning of the animal images,” I ask. “I had just been in Venice. For me, the architecture and paintings of this city reflect the ambivalence of beauty and fragility. On the one hand, the numerous churches that give the city something higher, more protected, and, on the other, the matter which is successively endangered by nature and civilisation. The animal images were integrated both on the basis of their biblical significance and as a fundamental symbol for nature,” explains Schweizer. And that’s the image content. But the excitement of the image carriers and their presentation form is also exciting here: “In order to express the fragile, fragile also in terms of the material, I experimented with digital prints behind glass during this first Venetian work cycle. It was important to me to develop a presentation form supporting the overall statement. That’s how I got the idea of a console that supports the glass picture like an altar. The tilted position creates light from the back, which gives the colours a stronger luminosity than directly being attached to a white wall would have allowed.” The images do in fact have an enormous amount of luminosity. They positively radiate! An analogy for atomic radiation? Oh yes – the title by the way is Frozen light.

The first fleeting glance at the second Venetian work cycle Hiroshima Morning does not at first show that this could have resulted from the same collages. Newspaper acts as a carrier material here. But the pages were not taken from any newspaper, rather from those published on the occasion of the seventieth anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima in Japan. Two worlds seem to be literally bumping into each other …

Lower row, Image 1: Box with the 50 collages of the Venetian series, Image 2: Paper 6 (PROMETHIUM) of the series Gefrorenes Licht (Digital print behind glass) 2014-2016, Image 3: Bild 24 (SEABORGIUM) of the series Hiroshima Morning (Digital print on newspaper) 2014-2017

Time for a summary.

The metaphorical references in the works of Helmut Schweizer seem almost endless and his enthusiasm for experimenting is limitless. In addition to what I have seen today, his now 50-year-old work also includes room installations, video work, photographic printing, public projects … The common guiding principle is now clear to me. But. Is there perhaps another formula that ultimately connects all thoughts?

In retrospect I notice that the threatening contents of his works are always superimposed on a sensual aesthetic. Beauty and horror are always united in some way. How important is the process of creating the works, I ask myself now. The “end products” that I saw all developed through experimental processes. In the most varied of ways, Schweizer has invaded materiality here. Has accepted changes and destruction – in order to create new results. The parallel to scientific research suddenly becomes apparent.

It is not only the actual state of the works of art, but also their experimental process of creation, which incorporates the time factors of change and transience into the works, and thereby questions the consequences of scientific progress responsibly and always critically. At the same time, new, imaginative, sensual images emerge within this process. It is a kind of energetic transformation that creates something positive out of something negative. Developed from a perspective that does not look backward resigned into the future, but forward … with images of hope …

>ARMAGEDDON · DAS URAN MUSS IM BODEN BLEIBEN · Lab ORATORIUM · eine Italienische Melancholie · für Giorgio de Chirico & Ettore Majorana<, Gruppe I >ATOME IN DER FAMILIE<, 2014-16 : v. l. n. r.: Fig.07 [Lise Meitner],Fig.09 [Fritz Straßmann], Fig.08 [Otto Hahn], (Photographie in Museum Kunstpalast Düsseldorf, Mike Christian)

Further Information

Works Helmut Schweizer_Galerie Rupert Pfab

Current exhibition at Ratingen until 21st February 2021: hiroshima-endlager-1945-2020