Today I am off to the Werden district of Essen. Situated in an idyllic green landscape right by the Ruhr, an avenue leads me to the former Krupp Stahl AG waterworks, now the home and studio of the Brus family. Behind an entrance gate lies the listed industrial heritage building. Sculptures dotted around the property point clearly to the workplace of Johannes Brus, one of the great graduates from the Düsseldorf Academy of the 1960s. He has been successfully established in the art scene as a photographer and sculptor for over 40 years now.

Image 1: Entrance to the sculpture studio – Image 2: Five Sculptures, 2004–2006 – Image 3: Elephant Head, 1986

He and his wife Monika welcome me. Is it obvious even at the entrance – the people in this house live for art. Photographs on the wall, an almost life-size sculpture of a horse in the hallway and the <em>Igor and Olga</em> sculpture on an old Chinese chest form the auspicious ensemble in the reception area. Only a glass wall separates this from the living space, where several <em>Brancusi Paraphrases</em>, which I have just seen in the Lehmbruck Museum, can be identified. I have an increasing sense of anticipation.

untitled

First of all coffee is brewed, and while I wait for this I am allowed to look around at my leisure. Living and working go hand in hand here. The architecture fascinates me as much as the art. Only individual glass walls and a gallery have been built into the former industrial hall, creating transparent separate rooms and a second level. Large arched windows let the sun flood in and reveal a view over a number of old trees.

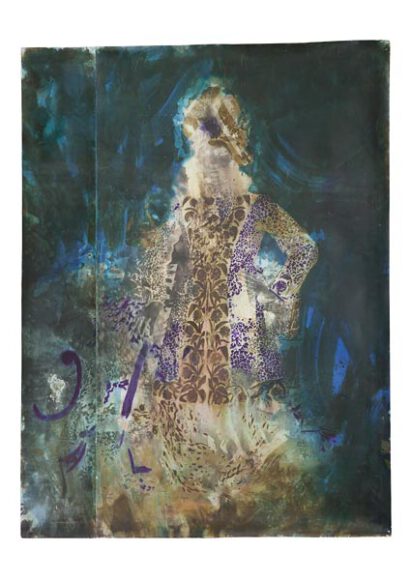

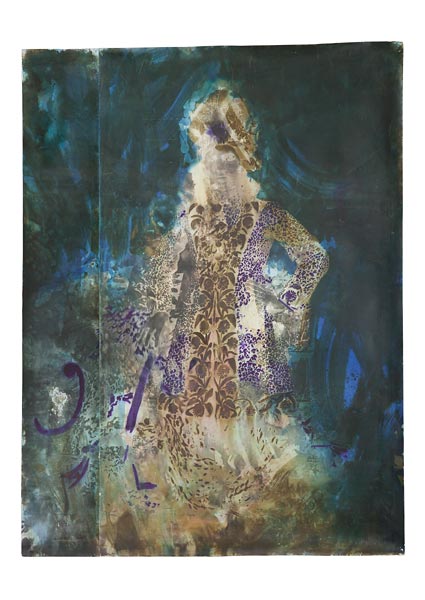

In the partitioned spaces behind the dining area and the sofa it looks like a working area. Numerous photo prints and cuttings from prints lie on the table along with colour toner, developer, scissors and – an iron (?). Scattered on the floor and leaning against the walls are large rolls of paper – presumably more prints. These may well all be the ingredients that constitute one of Brus’s characteristic photographic works?

Johannes Brus comes over to me. In response to my declaration that I like the <em>Ghosts Cloth</em> in his current exhibition so much, he singles out one of the paper rolls, and unrolls a variety of <em>Ghosts Cloth</em> prints onto the floor. Solid, rusty (!) iron bolts act as paperweights. Brus sees my horrified look and laughs: “I always like doing that when gallery owners come, too. My works have to be able to cope with it.” He is right. They have to, judging by the demonstration I have just been given. With a dissatisfied look he regards the print lying in front of us: “I shall have to wash it off again, and do a bit more work with the brush.” “What, wash it off? Where? ” I ask, regarding its enormous dimensions. “In the bath,” is the answer I get. As this process is being demonstrated to me I pose the practical question of whether the wet paper might not tear, to say nothing of when he uses the brush. “Of course. It can happen. Then that’s it.” What a scary thought…

Maharajah, 2002

But it is precisely these experiments that give his work their special enchanted mood and make every print unique. As far as processing pictures is concerned, anything goes. So negatives are sometimes printed sharp, sometimes blurred; positives are turned back into negatives; colours are adjusted with toner; contours are traced or smudged with a sponge, made into collages or reworked later with black or white lacquer. Bearing this in mind, this certainly explains all the equipment lying around.

But now we head for the coffee table.

Elke Backes and Johannes Brus

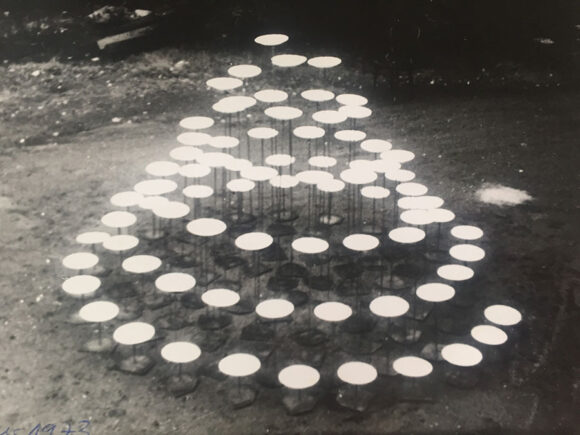

It quickly becomes clear that Monika and Johannes Brus are a well-established team. They entertain me by telling me about their beginnings and I become immersed in the art scene of the 1970s. One major landmark was their participation in the <em>14×14</em> exhibition at the Kunsthalle in Baden-Baden. The <em>Spiral of Plates</em> had to be produced for this very quickly. That meant getting hold of 80 pure white (!) plates, casting 20 – 30 polyester cucumbers and digging out several square metres of lawn and bushes. Everything had to be presented just as it looked in the sketch. “Besides buying plates and digging up a lawn, the worst thing was the stench in our apartment. Our oven was broken. It wasn’t possible to prepare any food in our kitchen for weeks,” says Monika Brus, rolling her eyes. The reason for this was that the lack of time made it impossible for the polyester to be cured conventionally. So then the oven had to be used to speed things up… “But that was the way things were then,” her husband explains the chaotic attitude that is prevalant. “We tried a lot of things. Sometimes it even happened that an oven bit the dust and you risked a chemical accident. We didn’t take everything all that seriously. ” This takes us right into the next story.

Spiral of Plates

Brus recalls a joint exhibition in London. “There is a catalogue,” and immediately he goes to look for it. Soon after this, the catalogue is spread out in front of me. It is a compilation of A4 photos. And what photos! Iconic is not the word. They are historical documents from the hippie era. Together we scroll through the pages on which all, absolutely ALL the well-known protagonists of the art scene in Düsseldorf and Cologne can be found. Monika Brus, who at that time was studying sculpture at the Academy just like her husband, points at the individual figures with amusement. Wow! I think to myself, and wish I had a time machine that could let me be there at least once. I could carry on listening for hours, but – visiting the artist’s workroom also involves visiting the sculpture studio.

Image 1: Dancers, 2015/16 in front of Brancusi-Paraphrasen, 2002 – Image 2: Elephant Head, 1986

This sight reveals a paradise for any fan of Brus. They are all assembled there: <em>the Dancers</em>, framed by <em>Brancusi Paraphrases</em> and <em>Ghost</em>, animal sculptures in all variations and of course the <em>Inspector</em>, who seems, with her look of sublime arrogance, to have the entire scene under control. There are experiments here, too: with material, shape, surface, and – of course – with colour again. “How do you achieve a colour structure like this?” I ask in amazement, looking at one of the <em>dancers</em>. The answer is similar to the one given before when we were talking about editing photographic images, although this also involved an unintentional experiment. “I accidentally spilled a cup of rose hip tea on the figure. After the initial shock, I was thrilled with the result it created. That was an entirely new starting point,” relates Brus enthusiastically. I wouldn’t be surprised if photo prints weren’t showered with tea in the future…

Bild 1: Inspector, 2008–11 – Bild 2: Detail Dancer, 2015/16

Finally, I would like to know what it it is about cucumbers, which are so often to be found both in his photographic and his sculptural works. “What started that was a book by Schrenck- Notzing which was circulating around the Academy at some stage” comes the explanation. “Parapsychological experiments were suddenly the big topic. Setting things in motion with hypnosis. And we wanted to carry this through into our art. Why not simply turn the classic still life around and, instead of “still” fruit, depict moving fruit? But I did not want any fruit that is already being used for this subject, which is why I picked the cucumber. ” This then explains the legendary images of flying and dancing cucumbers above the wooden table in Brus’s garden. Emerging from these images, then, came the idea of also transferring the motifs into sculpture. Ever since then, his photographic work has been the main impetus for him in his sculptural work.

Sheet cut from Cucumber Party, 1970

Photography as an inspiration and template for sculpture? Or conversely, sculpture as an inspiration and motif for photography? A simple question of which inspired which? It suddenly occurs to me that this is one of the key questions of scholarly research into art. And the cucumbers that are flying or balanced? The “moving” still life? It suddenly becomes clear to me that hiding behind this is one of the key challenges faced by artists for centuries. – It is the split-second representation of a movement!

But looking back on my visit it seems to me that Johannes Brus’s art somehow responds to these great questions purely by accident. And it is exactly this efortlessness that defines his work; which must have inspired both his artist friends in the 60s and his students during his time as a professor at the Brunswick Art Academy. His art can be fun, or can also be explored in depth as a part of art history. It depends entirely on the observer…

More Information

… about the Exhibition at the Lehmbruck Museum “Probe zu: Tanzen für Brancusi” (Rehearsal: Dancing for Brancusi) (in collaboration with the DKM Museum DKM) March 2016: http://www.lehmbruckmuseum.de/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/Pressemappe-Johannes-Brus-Website.pdf

his early works in particular are on show until 29 October at the TZR Gallery in Dusseldorf. http://www.tzrgalerie.de/blumebrus.html