The confrontation with the inside, the outside, and the trappings

Text: Dr. Elke Backes, Photos: Markus Schwer

Where do you start and stop? When do you have the chance to talk to an artist whose work is as complex, extensive and significant as his? Alfonso Hüppi is one of the most important representatives of post-war avant-garde and post-modernism, and is as gifted a painter as he is a sculptor, draftsman and graphic artist.

My initial idea of trying to narrow down my questions fails with his answer to whether there is a group of works, or creative period, that is particularly close to his heart. “No. Somehow everything has a story and is therefore significant to me”, making it immediately clear that one can only approach this Œuvres by talking precisely about these stories.

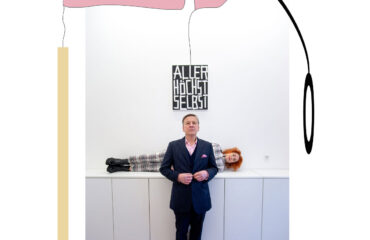

And that’s what we do while we have coffee and cake, browsing through his beautiful studio in Baden-Baden. The loft airiness and generosity create plenty of space for all the machine for handcrafts, tools, and works. It is a perfect setting. You can literally breathe the working process.

Studio Impressions

Hüppi told me right, at the beginning of our conversation, that he literally needed many detours before his artistic career took off.

Hüppi: It took me quite a while before I knew what I wanted. I thought it was wonderful to create objects with my own hands so I decided to do an apprenticeship as a silversmith. Virtuoso experts tought me the craft in four years. One day my boss asked me to design a vessel. When he measured the design, he rubbed his eyes in amazement: “It’s all in the golden ratio.“ From then on, all drawings and designs were assigned to me.

After four years of apprenticeship, I changed to a „Meister“ who was a painter, sculptor and church goldsmith. Three years of lively collaboration followed, but I was still searching for a way to complete artistic freedom. I enrolled in „Hochschule Pforzheim“ with the sculptor Josef Weber. A strict and uncompromising professor to whom I owe much. After two semesters, it was clear to me that I had to leave all bourgeois customs behind, and do what I was most afraid of: traveling to foreign countries without money, planning, security or language skills.

I started hitchhiking over the mountains towards Italy. Sitting among pigs, I arrived in Greece. After months of adventurous travel, I finally stood before the tomb of Hafis in Shiras, which I visited decades later with my students to pay tribute to the great poet. The book “On the Way to Hafis” was born out of this encounter.

The way back across the Black Sea ended in Hamburg. By chance, I discovered the study of calligraphy at the academy. After one year, I was a lecturer in the subject, and then in visual design for two years.

Dietrich Mahlow finally invited me from Hamburg to the „Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden“ in 1964. I was responsible for designing all catalogs, posters and publications. Exhibition preparations put me in touch with many artists. Visits to Hans Arp, Emilio Vedova, Antonio Music, Madame Puni, Tadeusz Kantor, Richard Huelsenbeck, and many others, were tremendously enriching to me.

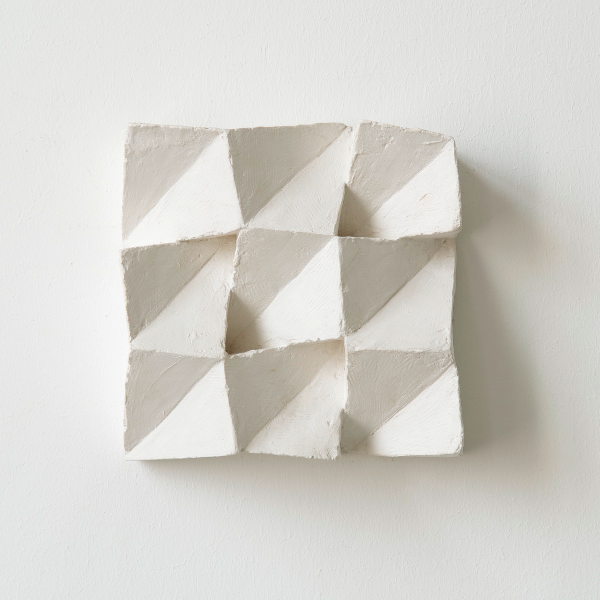

E.B.: Against this background, the plaster relief „Pyramid“ can now also be read as a homage to ancient culture. It is often regarded as your key work, because it shows your preference for clear forms and the idea of finding new forms through deconstruction. Pallets and crates, in particular, often formed the basis for this process. What was it about these objects that appealed to you?

Pyramide (1958/1959)

Hüppi: The confrontation between the inside and the outside. Rejecting the outside, attracting the inside. These are two enormous forces that you have to deal with.

E.B.: Were you reversing the balance of these forces, depriving them of their characteristics, tricked them, so to speak?

Hüppi: You could also say, I showed qualities that were hidden [smiles mischievously].

E.B.: Didn’t you miss the experimental in calligraphy?

Hüppi: No. On one hand, I have always been active in sculpture and painting, and on the other hand, you can also find the experimental in calligraphy. Here, you can experiment with line, which one learns to observe very closely. I have developed an awareness of how the stroke of the line changes depending on the direction, and the importance of the spaces around. This awareness forms the basis of focusing not only on the form, as such, but also, and above all, what it causes and happens around it.

E.B.: Particularly evident in your writings and drawings is the filigree-like handling of the line. Also particularly apparent is the large-scale shapes in your woodwork. How did you actually come up with the idea of working with boards, pallets and wooden crates, of all things?

left: Sketch sheet in the studio (2021), right: Kiste (1965)

Hüppi: My office at the Kunsthalle was also my studio. I also wanted to paint there. So I bought canvases and set off to work. But I immediately felt that the material didn’t do anything for me. The malleability of the surface – that was no challenge for me. So I looked around. Right next to my office was the Kunsthalle’s warehouse with lots of packing material. I immediately set my sights on a particular board that the janitor used to handle the coal wheelbarrow over the steps. I just stole it and he was pissed off. His name was Tullius. When I named all the work of that time Tullius, he didn’t know whether I was trying to make a fool of him or maybe feel honored [laughs].

I still have this first board here. Also the first box …

The “Ur” board on the way to the photo shoot

The board that is prepared for transport, leaning against the wall, is unpacked without further do, and moved to another setting for the photo shoot. It is undoubtedly a beautiful work, but when you know the story it becomes auratically charged. It’s the same with the “Ur” box that Hüppi shows me next.

Hüppi: It actually originated from the first pallet I worked on, which had paper piled on it.

The „Ur“- box (1965)

E.B.: The color scheme, and the idea of using consumption materials, remind me of Warhol’s Brillo Box, i.e. Pop Art. When I look at your early designs, developed from deconstructed boxes, I immediately think of the Ulmer Hocker, an icon design by Max Bill. Was there a connection to this stool?

Entwürfelung left (1974/1975/1976), right (1976)

Hüppi: In terms of idea development, there was none. But I was friends with Max Bill. Our meeting was also a special story: we had met by chance at the home of my gallery owner Hans Mayer. Bill asked me what I was up to at the moment. I replied that I was preparing an exhibition in Hamburg. When he spontaneously offered to give the opening speech, I was totally surprised. I had not imagined that he could relate to my work.

E.B.: Your circle of friends includes other famous artistic personalities such as André Thomkins, Jean Tinguely, Daniel Spoerri and Dieter Roth. Did you influence each other?

Hüppi: We were all very stubborn, so not so much. However, there have always been joint projects, mutual support, and works dedicated to each other.

Examples of works created in the context of the artist’s friendships: left: Turm der Liebenden(1997), „Il Giardino di Daniel Spoerri“ in Seggiano, right: Tor für Max Bill (1993)

E.B.: Speaking of headstrong, or perhaps better said individual, you were a professor of painting at the Düsseldorfer Kunstakademie for twenty-five years. Looking at the list of those who emerged from your class, one finds significant names such as Thomas Rentmeister, Markus Oehlen, Monika Baer, Holger Bunk, Corinne Wasmuth or Claus Föttinger. All of these artists have very distinctive works. How did you contribute to this?

Hüppi: It was always important for me to motivate the students’ power of observation and to look at what goes beyond their own work. That’s why the study trips were such an important part of my training.

E.B.: These trips are considered legendary. In addition to the typical study trips, you also traveled to countries such as Tunisia, Turkey, Egypt, Iran, Syria and Armenia. Was the choice of destinations influenced by your own travel experiences?

Hüppi: Absolutely. I wanted to give my students this opportunity because the experiences in these particular countries had made such a strong impression on me. When you travel for three weeks with a bunch of crazy people and spend the night in the most abstruse places, you simply experience adventures that stick in your memory forever and also shape your personality. And this is ultimately reflected in the individuality of the work.

E.B.: Another unusual art support related to travel, was the founding of your project Etaneno – Museum im Busch in Namibia. How did this idea come about?

Hüppi: It came about when visiting my friend Erwin Gebert on his newly built farm in Namibia in 1998. He had fulfilled his big dream to retire there after decades of working as a freelance architect. At sunset, we sat together on the terrace – with a bottle of whisky – and he asked me what he should do now. I said, “Why don’t you build a museum?” His answer: “I will!”. The next morning, when we were sober, I was more than surprised that this suggestion was still being considered and that eventually it was realized. Starting in 1999, I traveled twice a year with six artists to work in the bush. In 2011, the majority of the works, combined with an exhibition, were given to the Museum of Contemporary Art in Freiburg im Breisgau, another part to the Museum Windhoek.

Etaneno – Museum im Busch in Namibia

E.B.: You handed over your own work to the Van Ham Art Estate in Cologne in 2020. Five hundred works are already being researched there, and they are making sure ensure that they continue to be presented institutionally and made accessible to the art market. As one can easily see here, you still have some logistical work ahead of you to prepare the remaining works still in your studio. Does this mean that your artistic work is finished?

Hüppi: By no means. I’ve been drawing and painting ever since I was able to hold a pencil, and I won’t stop for as long as I can. Whenever I am in the mood, I let words or lines flow onto paper, which then somehow find their way to shape and perhaps later lead to new objects. I also continue to work on unfinished sculptures, watching what happens when I take something away, add something, or take something apart. Same as always. I never want to lose this self-awareness. It’s like breathing for me.

Insights into current work processes

So it does exist. The common core, apparently hidden, can be recognized retrospectively, throughout all of his anecdotes.

It is the everlasting confrontation with the inside, the outside and the trappings, that is the common denominator of his work. Despite all the diversity, every artwork which is “breathed out” always bears the unmistakable signature of Alfonso Hüppi …

Further Information

Artisttalk: Wibke von Bonin with Alfonso Hüppi, 2.9.2021, 18 Uhr

Artist Website: https://www.alfonso-hueppi.de

Van Ham Art Estate: http://www.art-estate.org/

Representing Galleries:

Galerie Henze und Ketterer: http://www.henze-ketterer.ch

Galerie Rupert Pfab: https://galeriepfab.de/

Galerie Reinhold Maas: https://galeriereinholdmaas.de

Galerie K: https://galerie-k.art