Photos: Markus Schwer

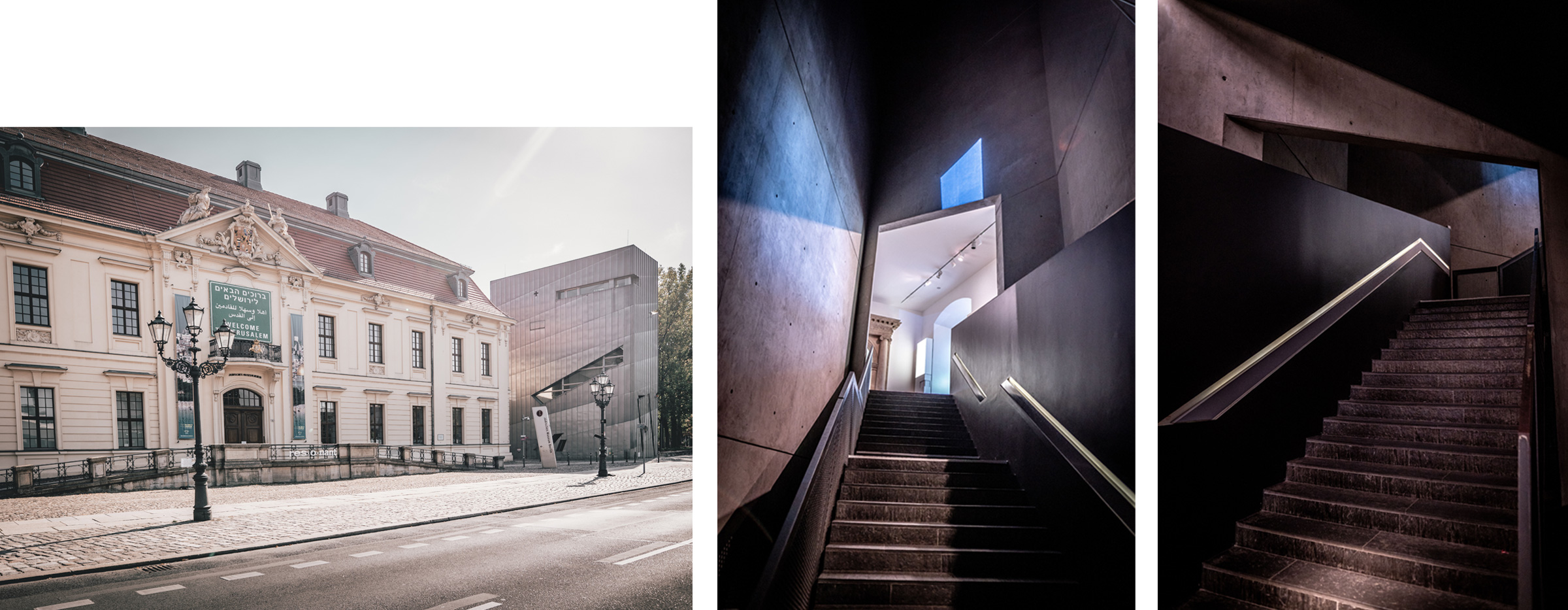

Berlin, Jewish Museum. I have an appointment with Mischa Kuball in the Libeskind building, one of the contemporary architectural icons of Berlin. His light and sound installation res·o·nant, specially created for this location, remarkably illustrates the working method of this conceptual artist, who has been presenting his artistic statements in public and institutional spaces since 1977.

The question of whether the German National Museum of History, Religion and Central European Jewish Culture can properly take up an area of 350 square metres without displaying anything is currently the subject of controversial debate. Can a light and sound installation do justice to the special cultural mission of this institution?

(c) Foto Archiv Mischa Kuball, Düsseldorf

The first way to answer this question, I soon realise, is to invite the artist to view the installation, which has a major impact on the exhibition galleries of the entire building.

We meet at the main entrance, which is located next to an old baroque building, and together make our way to the exhibition space. The passage to the new building is through a staircase to the basement. A radical change of building materials and lighting delimits this transition. The rough, dark concrete walls and the accentuated, weak light in the staircase are replaced in the basement by white walls and a bright light.

We encounter three crossing sharp-edged axes. The name of these axes, which are inscribed in the building, underscores the history of Judaism: the “axis of continuity”, the” axis of exile,” and the “axis of the Holocaust.” The floor seems to slope upwards, the walls are crooked, and as we move, everything seems to be moving. A two-part mirror positioned at the intersection of two axes, which cuts through the upper and lower sections, causes further irritation. It then reveals itself, aligned, as a signpost to the exhibition space: res·o·nant.

To understand the installation concept by Mischa Kuball, it is important to have a floor plan based on two lines: a zig-zag line often visible on the building itself and an invisible straight line. At the respective crossroads are the so-called “Voids”. These are 24-metre-high voids extending from the basement to the roof, symbolising the human emptiness caused by the Holocaust, the expulsions and the pogrom. Two of the five voids, which have been neither accessible nor visible to the public since the opening of the building in 2001, as well as a void at the entrance to the old building, are taken up by the res·o·nant lighting and sound installation.

Drawing by Daniel Libeskind

“What were these rooms used for?” I ask before entering. “There was an educational center, which had been completely restored to its original architectural design. Aesthetically, it had something of a Westphalian savings bank. In order to be able to deal with the space, it was necessary for me to remove everything first,” Mischa Kuball explains.

I enter the room with excitement. It gets dark again and noticeably colder. We pass an elongated wall display case. With the exception of a few loose cables, it is empty.

The path forward is determined by the lighting. On one side, there is daylight flowing through the void and on the other side, there are round and rectangular shaped, rotating fields of light. On the left side, the wall opens to the adjoining room, which is completely immersed in dark red lighting. The repetitive, echoing “clicking sound” of the projector breaks through the silence, as well as the particular 60-second sound clips, which were specially produced for res·o·nant by 220 musicians from all over the world. Sounds, noises, and sometimes only voices seem to meander, in a ghostly way, through the exhibition space.

I move on to the light shaft as if guided by a remote control. While the ceiling height (fit for a museum gallery) is perceived as restrictive, the void now opens up to the roof and directs my view up towards the infinity of the sky. The moving fields of light that I perceive in the corner of my eye bring me back to the present. I suddenly see myself in the middle of a circle, an unequal rectangle moves around me.

“The different layouts of the voids are traced with the rectangular shapes. The circle symbolizes people for me. The lighting projections are redirected by mirrors in the room. So there is always a common reflection of both shapes. With this, I would like to raise awareness of the fact that an individual always moves in a context “, Mischa Kuball explains. I hadn’t even noticed the rotating mirrors before. Nor had I noticed that the light color in the red glowing adjacent room repeatedly rises until strobe-like flashes causes a kind of a discharge. Everything happens slowly and quietly.

“I don’t want to stun the visitors with light or sound, but to create moments of self-reflection”, Kuball explains his intention. “That’s why I am not exhibiting anything, but simply accentuate the space for the person who enters it. It is incredibly exciting to see the different reactions of the people. Some walk around looking for objects, while others lie down in the middle of the room and immerse themselves completely. Yet, others move to the sounds as if in a trance. It is interesting to observe the dimensions of mediatisation. Everything is photographed and filmed: the space, you and the people around it – all in all a very special form of interaction,” says Mischa Kuball.

As so often in his projects, res o n • nant mediates between audience, artist, work and public space. For Berlin Art Week, he extended the installation from the museum into the urban space, making visible the historical references that had influenced Libeskind’s building design.

(c) Fotos: Archiv Mischa Kuball, Düsseldorf

The museum’s first-time participation in Berlin Art Week this year can be attributed to a change of focus, which is increasingly opening to the outside. The discussions around the designing of the programme continue not stop. The fact that the Jewish Museum, in addition to focusing on its collection, also opens up to such explosive topics such as global migration, and the tensions arising from the interaction of minorities and the society at large, is often criticised. What is the role of res • o • nant in this context? I ask Gregor Lersch, the curator of temporary exhibitions, who joined our conversation.

Elke Backes, Gregor Lersch, Mischa Kuball

“The basic idea was not only to open the Education Center, which had been inaccessible to the public, but also to enable visitors to experience it through art interventions. Mischa Kuball’s task was, therefore, to conceive a spatial installation that would follow Daniel Libeskind’s central guiding principle. The idea had been developed during the reconstruction of our permanent exhibition space. Within the framework of our two year alternative exhibition programme, we decided to try something new. We were aware that a light and sound installation – without an obviously recognizable mediating element – could cause irritations. “

And probably also intentional, I think in retrospect. Irritation as part of the installation of res·o·nant., created and visualized through the architecture of Daniel Libeskind

By minimizing the space to the elements of light and sound, Mischa Kuball turns the emptiness of the architecture tangible; it is an emptiness that raises questions about our own point of view in history and, increasingly, makes us aware of our surroundings. Emptiness, darkness, red colors, lightning, even cables lying around in an empty display case, are suddenly connected with visual and literal memory, which causes goose bumps.

Are exhibitions still needed to fulfil the cultural mission of the museum?

The installation can be viewed until the summer of 2019. Responsible program director is Leontine Meijer van Mensch.

For further information:

… about the artist: www.mischakuball.com

… about the installation: